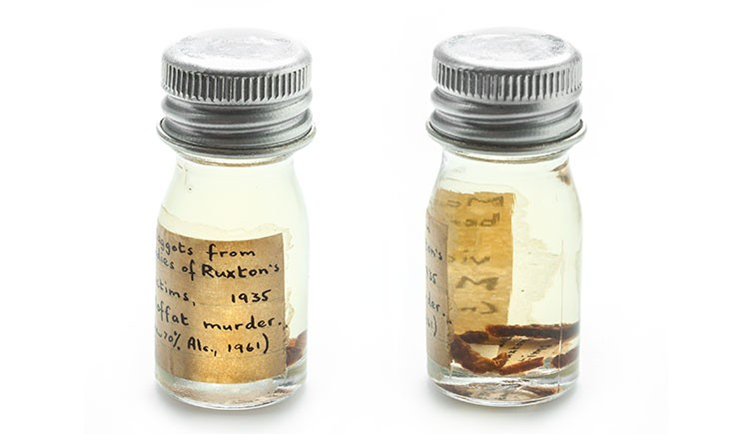

The Ruxton Maggots

During the investigation, various maggot specimens were collected from the remains and sent to a laboratory at the University of Glasgow. It was there that specialist Dr Alexander G Mearns identified the species as Calliphora vicina, more commonly known as blowflies – or bluebottles. By examining the maggots, it was established that they were somewhere between 12 and 14 days old, thus confirming the probability that they were deposited at Gardenholm Linn around the 16th September.

This was the first time that maggots were used in a forensic investigation in the UK and proved to be of enormous significance.

The Ruxton Maggots were preserved and are part of the Natural History Museum’s Permanent Collection, underlining their enormous importance. They were loaned to Moffat Museum for this Exhibition.

Additional Detail from Dr Erica McAlister

Senior Curator at The Natural History Museum

“Although these maggots were used in the earliest UK recorded criminal prosecution using forensic entomology, this was not the case for mainland Europe who had been successfully using insects since the middle of the 1800s. In Germany and France after many turbulent periods, there were sadly many mass graves of unidentified individuals were finally being exhumed, and doctors were noting the arthropod fauna associated with the cadavers.

“But it was in 1855 that the French Dr Louis François Étienne Bergeret or Bergeret d’Arbois as he was more commonly known who first used this knowledge to help successfully defend a couple who has discovered a child’s body in the wall during some home redevelopments. Luckily for the couple, d’Arbois was able to create a time frame thanks to the insects which predated the couples’ time in the house and helped shine the light on the previous tenants.

“D’Arbois was not an entomologist but he helped start a revival in understanding about forensic entomology, and one such fellow inspired by this case was Jean Pierre Mégnin, a French army veterinarian. Not only obsessed with dogs, but he was also fascinated with entomology, particularly that associated with cadavers and in 1894 published the ‘The Fauna of Cadavers’ which detailed eight waves of succession on both buried and exposed corpses – and in doing so the modern era of forensic entomology had begun. “

The Ruxton Maggots – collected by Professor John Glaister at Gardenholm Linn in 1935 and now part of The Natural History Museum’s Collections (Specimen Registration : NHMUK 010198316).

Further detail : ENTOMOLOGY

Calliphora vicina is a member of the family Calliphoridae, which includes blow flies and bottle flies. These flies are important in the field of forensic entomology, being used to estimate the time of a person’s death when a corpse is found and then examined. Calliphoravicina is currently one of the most entomologically important fly species for this purpose because it arrives at and colonizes a body following death in consistent timeframes.

These flies can detect death from 10 miles away.

A great many species of fly feed, in their larval or maggot form, on what is known as “carrion”. But those capable of detecting death from as far as 10 miles away and are therefore often the first to find a dead body, are those of the family Calliphoridae, better known as blowflies. In Britain, they include the common bluebottle and greenbottle, and they are the forensic entomologist’s raw material.

Underlying the science is the helpful fact that flies go through four main and identifiable developmental stages, from egg (which will generally hatch within 24 hours) to larva (which will feed on the corpse for about five days, then spend another couple preparing to pupate) to pupa (equivalent to a butterfly’s chrysalis; another seven days) and onwards to adult fly. The maggot stage, in particular, can be further subdivided into three distinct phases, known as instars.

The exact rate at which a fly develops through these stages can vary significantly according to a number of factors, notably the temperature at the scene, the size of the body, whether it is in the open air or in a sealed room, and whether it is naked or clothed. The forensic entomologist’s basic job, then, is to collect and measure the insect life on and around a dead body, factor in all the variables, and come up with an approximate time for when the first flies arrived on the scene. After about three days, it can be difficult for a pathologist to judge the time of death. Using insects, it is possible to be accurate to within a day.